This article by Manny Robinson first appeared in the Greenville News

There is a pipeline firmly embedded between South Carolina and Georgia. Recently, the Clemson University football program has utilized it to syphon top recruits from across the border. Clemson plucked Deshaun Watson, Mitch Hyatt, Tre Lamar and Trevor Lawrence from the Peach State. Those native Georgians helped Clemson win two national championships.

In 1965, just as many recruiting gems flowed through that pipeline, but in the opposite direction. The University of Georgia plucked a coveted crop of players from the Palmetto State. That year, Georgia signed Kent Lawrence from Daniel High near Clemson, Wayne Bird from Florence, Pat Rodrigue and Steve Farnsworth from Greenville and Steve Greer and Steve Woodward from Greer.

“Frank Howard had been recruiting me since I was a freshman in high school,” Greer recalled, referring to Clemson’s longtime coach. “South Carolina recruited us too, but we all liked Georgia.

“We got to know each other because we met somewhere every weekend, Georgia or South Carolina, Clemson or Tennessee, because there was no limit on the number of times you could visit back then. We all came to the agreement, ‘Well, we love Georgia. Let’s all go to Georgia together.’ ”

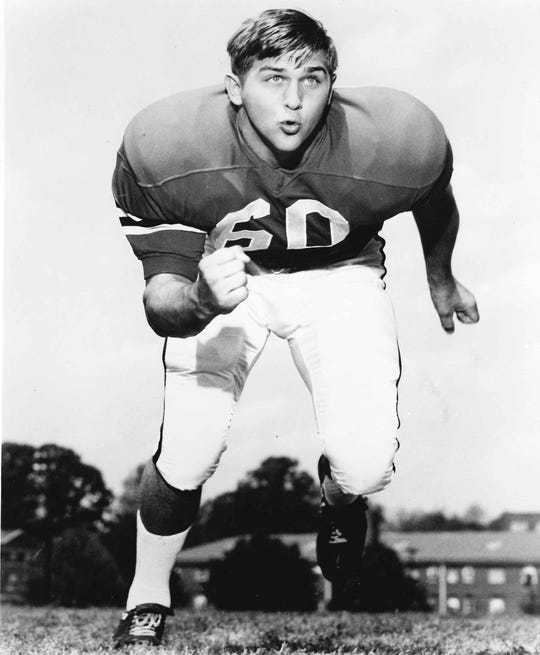

Howard, partially in angst but mostly in jest, began referring to the group of defectors as “The Knuckleheads.” The group embraced the label and helped Georgia win two Southeastern Conference championships in 1966 and 1968. Greer blossomed as a defensive tackle, although he was built more like a defensive back.

“When I came to Georgia I probably weighed 210 or 215, and then I had a knee injury my freshman year, lost a bunch of weight and really never gained it back,” Greer said. “The most I think I ever weighed was like 205.”

Nevertheless, Greer bravely placed his hands in dirt in the interior of Georgia’s Split-60 defensive front. He utilized his speed to outmaneuver larger guards and centers. He earned first-team All-American honors as a senior in 1969.

Greer was inducted into the UGA Ring of Honor in 2014. This year, he was nominated for the South Carolina Football Hall of Fame.

“In my opinion, pound for pound the greatest player I ever coached,” Vince Dooley, Georgia’s coach from 1964 to 1988 asserted in a nomination letter on Greer’s behalf.

Greer also garnered support from Augusta National Golf Club Chairman Emeritus Billy Payne, Greer’s teammate on the UGA defensive line, legendary UGA sports information director Claude Felton and many prominent civic leaders from the Upstate and Georgia.

All of Greer’s supporters lauded his grit, which outweighed his frame. The same determined spirit that propelled Greer past offensive linemen is guiding him through the toughest battle he has ever endured.

Greer was recently diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects the brain and the spinal cord.

“It’s a tough disease. There’s no cure for it, and they can’t tell you where it will go next,” said Greer, who first noticed symptoms of ALS after a second neck surgery.

Greer has lost the use of his right arm and is losing functionality in his left. Yet, he has not and will not lose his will to fight.

“I’ve just got to keep on keeping on,” Greer said. “Do the best you can every day and enjoy every day.”

“He’s got atrophy in his shoulders and in his arms, but you would never know it because he has the most positive attitude, much more positive than the rest of us do,” Greer’s brother-in-law, Gary Griffin, said. “That kind of diagnosis is not an easy one to take, but he’s really been a role model for everybody in the family with the way he’s dealt with this.”

When he is not traveling for treatments, Greer enjoys traveling leisurely with his family. He still adores hunting trips with his sons and grandchildren.

“Of course, I can’t shoot a gun. I can’t do a lot of things, but it’s good just to be there with them,” Greer said. “When we go fishing, I’ll shut up and sit in the boat and watch them. I can’t just sit on the couch and worry about the next step.”

Greer’s defiant positivity does not surprise his former teammates and colleagues.

“He was and is all heart and exudes impeccable character. This man is more than exceptional,” Greer’s former teammate, Thomas Lawhorne, said. “Steve is showing us all how to live and die with dignity and guts — not unlike his gritty performance on the gridiron.”

Greer relished every chance to convince skeptical guards who doubted him before the first snap, especially in his home state.

“We go up to play Clemson in 1967. Clemson comes to the line, and I’m on this guard,” Greer recalled. “They were in that pre-shift at that time, where they’d come to the line and put their hands on their knees, like the old Dallas Cowboys, raise up and then go back down in their stance. And when they raised up, this guy said, ‘God Almighty, I got me a baby lined up on me over here.’”

Greer remembered Clemson lineman Harry Olszewski using some other colorful language to describe him. Olszewski used even more colorful words after he realized Greer was not a baby, but a full-grown terror who helped Georgia earn a 24-17 win that day.

Three years later, Greer signed with the Toronto Argonauts of the Canadian Football League. He lined up for the first time as a pro in 1970 season opener against the Montreal Alouettes. He heard a familiar phrase roar across the line of scrimmage

“I go out for the first snap, and I hear, ‘God Almighty, I got me a baby lined up on me over here,’” Greer said with a laugh. “It was Harry Olszewski.”

Greer never lost a game to Clemson or South Carolina, a fact about which he reminded Olszewski that day. And he reminded Frank Howard of it a few months earlier. After he closed his career at UGA, Greer earned an invitation to the Hula Bowl, the postseason all-star showcase. Howard had recently retired from Clemson and served as a Hula Bowl coach.

“I loved Old Frank Howard. While we were out there (in Hawaii), he kept saying, ‘You knuckleheads all went over to Georgia,’” Greer said. “He was fun to be around, and he always remembered ‘Greer from Greer.’”

Greer crossed paths with Howard often as Howard spent the early part of his retirement on a coaching clinic tour. Greer opened his coaching career at Auburn. He spent seven years on the other side of that rivalry before returning to Georgia in 1979. Greer assisted Dooley and his beloved defensive coordinator Erk Russell.

Georgia won the national championship in 1980. Greer remained on the UGA coaching staff until 1993. He then moved to an administrative role. He retired from that position in 2009.

The City of Greer is named after one of Greer’s ancestors. He still cherishes it as his hometown, but he has also been adopted as a Georgian. He and his wife Susan will soon celebrate their 50th anniversary in the same home they built together in Athens in 1979.

Whenever he visits the treatment facility in Augusta and observes ALS patients in more advanced stages, Greer wonders what the disease will steal from him next. But when he thinks about Susan, his three sons, his six grandchildren, his family, friends and former teammates. When he thinks about the players he mentored. When he thinks about the lessons he learned from Erk Russell and Vince Dooley. When he thinks about those five players he ventured to Georgia with in 1965, he knows he can never let ALS steal his heart.

“You just continue to fight it until you can’t fight it